PARSIPPANY’S MUSE

Henry Inman, Unidentified lady, c. 1835. Oil on canvas. Collection of the New-York Historical Society. Used with permission.

As dusk settled over the dozen or so dwellings clustered along Parsippany Brook, locals and visitors bundled against the cold began to congregate in front of the brick Academy building. This small community had every right to be proud of its theater, newly installed in the school’s upper room, and of the homegrown talent that would bring the night’s dramatic and musical offerings to life. But, while the crowd took its seats in excited anticipation, within the mind of at least one audience member there was much unease.

Twenty-year old Maria Caroline Cobb had viewed the approach of this “Academic Exhibition” with dread, as is shown by a solitary letter to her cousin, Walter Kirkpatrick, preserved along with several from the pen of her younger sister Julia Ann.[1] Maria’s letter replaced a much longer one that, for undivulged reasons, she never sent. “The circumstances I will omit for the present,” she wrote, but on the subject of what was to take place that Friday evening, March 19, 1819, “If you was in my situation, you would desire it was over.”

What aspect of the event so affected Maria Cobb? Was she pressed by last-minute tasks, perhaps compelled to ply needle and thread to help finish costumes for the performers? Did she feel burdened by the evening’s social obligations which, as senior female in the household of Parsippany’s most prominent citizen, she inevitably must bear? Or could her anxiety have somehow involved the man chiefly responsible for what was about to unfold on stage?

A boy of eleven at the time named Isaac Lyon would grow up to remember that man as the “grand Major Domo of the whole concern – manager, scene-painter, costumer and chief actor,” whose livelihood depended on keeping a general store not far from the Cobbs’ house but who, attaching more value to art than to commerce, mounted dramatic productions out of his own meager funds. It is thanks largely to Lyon’s recollections, published a half-century later, that we know anything of Sylvester Graham’s theater, or of the time when this “eccentric and wayward genius,” whose fame would one day extend far beyond the bounds of New Jersey, once resided in the Morris County hamlet of Parsippany.[2]

A precarious childhood in New England and a history of poor health had left Sylvester Graham with a modest education and limited prospects. He did, however, display an early gift for public speaking and performance.[3] Although Lyon’s image of him as “gay and foppish in his dress, … a ladies’ man … [who] spent much of his time in wooing the Muses,” could not diminish his regard for Graham’s talents as an actor, orator, musician and author of prose and poetry, one of Graham’s earliest works stuck with him, not for the quality of its verse, but for the circumstances surrounding its theatrical debut. What happened on a cold March night in the upstairs room of Parsippany Academy became, in Lyon’s retelling, “the theme of social gossip round many a village fireside for years after.”

Advertisement in Palladium of Liberty (Morristown), March 18, 1819, of two plays to be performed at Parsippany Academy on the following evening. From the collections of the North Jersey History Center, The Morristown and Morris Township Library.

Graham decided to add to the two British plays already on the program a Supplement he had written to a familiar ode from the eighteenth century called The Passions.[4] In Graham’s composition a young man’s thoughts and words lurch between melancholy and madness. Smiling through tears, he recalls the delights of a love that is past, but his calm turns abruptly to alarm:

“But where now is she?

O death! O misery!

Those foul, perfidious charms,

Now fill a rival’s arms –

Those lips that gave me kisses,

Now! now! a rival presses.”

As the lovelorn youth veered towards delirium so did Graham’s performance, blurring the line between author and character, and his final, climactic gesture would have confirmed Maria Cobb’s or anyone’s worst apprehensions. Gripped by a “mad frenzy,” he cried:

“Away, foul fiend! away! away!

Dost still pursue? – then let me die!”

Thus saying, he raised his steel on high,

And plunged it downward furiously.

It reached his heart, he drew it out,

And from the gaping wound the warm life’s blood did spout!

As Isaac Lyon recounted the scene, chaos promptly ensued:

When the actor stabbed himself and fell, his white vest smeared with blood, there was a terrible commotion among the audience – many of them supposing that Graham had really killed himself. Had the house been on fire the consternation could not have been greater than it was. A score or more of ladies fainted outright, and the rest raved and screamed like so many maniacs just broke loose from Bedlam. The scene was terrible beyond description, and for a few moments the tumult was sufficient to appal the stoutest heart. Doctors were called for – there were two or three in the house at the time – windows were smashed, and snow and water were used without stint. The doctors flew to the rescue, and numerous old-fashioned smelling bottles were brought into requisition. But after the first alarm was over it was found that nobody was killed, and but few were wounded – except in their pride and feelings.

What may not have been widely known at the time would soon become familiar to all, namely, that Graham had suffered rejection from at least one young lady of the place, and that he took rejection hard. Was what Lyon drily termed “that night of horrors” the product of a terrible miscalculation? Or did Graham really mean to revenge himself upon one or more of the objects of his attention, and indeed on the community as a whole? He may not have fully known his own mind, and the basis of his anguish cannot be determined with certainty. But papers of the Cobb family suggest that the roots of his misery, if not the impetus for his dramatic and desperate act, lay with Maria Caroline, or her sister, or by turns both of them.[5]

If such was the case, Graham had to contend with their redoubtable paterfamilias, Lemuel Cobb. Known as “Colonel” for his service in the New Jersey militia, and as “Judge Cobb” for presiding over the county’s Inferior Court of Common Pleas, the father of Maria Caroline and Julia Ann owned extensive tracts in the iron-rich Jersey Highlands. These holdings, and the growth of mining and ironmaking operations in them, had brought Lemuel Cobb great wealth and influence.

“Percipany” and the house of Lemuel Cobb, detail of a map by Cobb and Walter Kirkpatrick of iron mines and furnaces in northern New Jersey. Map MC-3-7. From the collections of the North Jersey History Center, The Morristown and Morris Township Library. Photo by Carolyn Dorsey.

Both of Cobb’s unmarried daughters were, like most girls of their station, expected to show “accomplishment” in literature, language and the fine arts, as well as the traditional feminine skills of dressmaking and embroidery. Both were sent away to boarding schools, but Maria, whether indifferent to the subjects on offer or resistant to the headmistresses’ policy of “strict attention … to the morals and manners” of their charges, did not remain under their roof for long.[6]

As a single letter of Maria’s to her cousin Walter has been preserved, it is only from four written by Walter to Maria while he was a student at Princeton that one glimpses anything of her interests or aspirations. She appears to have been drawn to science. When she inquired about the college’s famous Orrery (a mechanical model of the solar system made by David Rittenhouse), Walter replied with sketches and a detailed description of the device. An awareness of international affairs may be inferred from Kirkpatrick’s writing to her concerning troop movements at the outbreak of the War of 1812, and about the aftermath of battles in Europe. She was curious, too, about college life, an experience from which her sex largely excluded her.[7]

Walter Kirkpatrick, scion of a prominent family of Somerset County, was a young man of talent and promise. Graduating from Princeton in 1813, he served for a year as a tutor to the children of Henry Clay, Speaker of the House of Representatives, before going to work as a surveyor and attorney for his uncle, Lemuel Cobb. [8] It was perhaps while journeying to the Clay home in Kentucky that Walter penned this wistful meditation:

And as oft as I tread the shaded banks of the beautiful Ohio, while the chaste moonbeam falls upon its placid flood, and recalls the image of the pure, the gentle, and the lovely Caroline; my chief delight will be in the “memory of the joys that are past,” while Hope, fond Hope, will look forward to scenes of future and more substantial bliss.[9]

Close cousins Walter Kirkpatrick and Maria Cobb had grown up together, their lives and fortunes so entwined as to allow little room for an interloper. But Sylvester Graham maintained a close if unspecified association with the Cobb family during the years 1817-1821, even though his temperament could not have agreed with that of Maria’s dispassionate and exacting father. Late in 1821 Graham ventured to speak to the New-Jersey General Debating Society, of which he was a founding member, on the question of “the interference of parents in the matrimonial concerns of their children,”[10] a subject on which Lemuel Cobb perhaps had given him much to say.

Frustrated in love, the unlucky Graham found release in an outpouring of verse. Examples of his poetry, their authorship half-concealed by the signature “G. of New-Jersey,” appeared in many newspapers and periodicals of the early 1820s. Whether commemorating friendships, marking holidays or describing the natural beauties of Morris County, Graham would invariably return to a courtship whose collapse, he felt, was brought on by the malice of others.[11] In lines that appear maudlin to the unsentimental tastes of today, he brooded over the fate of one cut off from humanity and forgotten:

In a sequester’d, lonely wild –

Where even beasts shall shun it,

Shall be the grave of sorrow’s child,

And none shall weep upon it!

No generous hand, with pious care,

To friendship consecrating,

Shall raise the ‘storied marble’ there,

His name and woes relating![12]

Determined somehow to make a living from his art, Graham staged a program of solo recitations in Morristown in April 1822. It included The Passions, along with the notorious Supplement premiered three years before.[13] A month later the front page of a local paper carried another of his poems, but this one signaled Graham’s withdrawal from the scene. It began thus:

Parsippany, list! – for the tale I will tell,

Shall rejoice thee extremely to hear:

O! list to my lyre’s valedictory swell! –

The Bard thou hast hated now bids thee farewell! –

Farewell – with a smile and a tear![14]

The poet eventually returned to New England where he married, and was enrolled briefly as a divinity student. But from 1826 to 1829 he was again in New Jersey and, having had some training for the ministry, was engaged by Presbyterian churches in Belvidere and Bound Brook. He lacked, however, the full endorsement of the clerical establishment, which had misgivings about his fitness as a preacher of the gospel.[15]

In the 1830s Graham set out in a very different direction to achieve the fame that he had long craved: he became a prolific writer and was much in demand as a speaker on human physiology and its relation to diet – what he termed “the science of human life.” His program of vegetarianism expanded into a crusade against intoxicating liquors, coffee, tea, tight-fitting clothes and other vices, making him, in Isaac Lyon’s words, “one of the best known and one of the best abused men in New Jersey.” Well beyond the boundaries of the state and even the nation, the “Graham diet” – reliant on the use of coarse flour to guard against debility and disease – won a substantial following, but it also proved a ready target for mockery and satire, and even a stimulus to riot. As a critic of the American food industry Graham was far ahead of his time, but the messianic tone of his message descended directly from that earlier, prophetic contemplation of his own grave, with no “storied marble” to mark it:

And when he fills the lonely spot,

Shall friendship weep him never?

But by the busy world forgot,

His name shall be for ever![16]

The Parsippany poet could not know the ultimate truth of his words. While later centuries, grown far more conscious of the benefits of whole grains, have partially vindicated him, Graham would surely have despised the ubiquitous sugary cracker for which he is chiefly remembered.

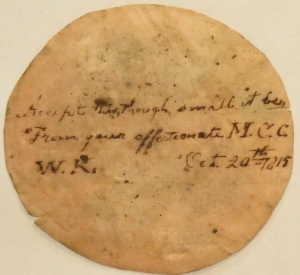

A miniature paper token sent to Walter Kirkpatrick by Maria Caroline Cobb, dated October 20, 1815. The watercolor on the obverse is inscribed “Friendship,” with Maria’s initials below; the reverse reads, “Accept this, though small it be, / From your affectionate M.C.C.” From the collections of The New Jersey Historical Society.

In January 1823, Maria Caroline Cobb and Walter Kirkpatrick were finally married in the Presbyterian church of Parsippany, but to Walter’s great sorrow the “more substantial bliss” that he had once longed for was brief. In October 1826, a week before her twenty-eighth birthday, Maria succumbed to a sudden illness, leaving her husband with a baby boy who less than two years later would also die unexpectedly, at the age of three.

Kirkpatrick lived on at Parsippany as a widower, serving as clerk of the township and of the church, continuing to work for Lemuel Cobb and, after Cobb’s death in 1831, handling the legal affairs of his estate. He subsequently married – again within the Cobb family – the daughter of Maria’s older half-sister Elizabeth. In 1832 or 1833 the Kirkpatricks moved to Walter’s ancestral home in Somerset County, and he served as a state legislator representing Somerset from 1836 to 1838. But family and business ties continued to draw him back to Parsippany.

The marker erected by Walter Kirkpatrick to his wife Maria Caroline and their son Eugene Walter Kirkpatrick. Vail Memorial Cemetery, Parsippany. Photo by John Zielenski.

There in the former churchyard, now called Vail Memorial Cemetery, Kirkpatrick raised to his first wife and their child a large marble tablet, unadorned except for an eloquent, two-part Latin epitaph. The inspiration for its first line is clearly Horace’s Ode 2.14 (“Eheu fugaces, Postume, Postume”). The rest seems to be an original composition, but it is steeped in the rhetorical technique of the ancients:

DELICIAE, EHEU FUGACES!

CONJUGIS

maxime amabilis et amatae,

prudentia eximiae,

officiisque omnibus

filiae, uxoris, matrisque

praestantis,

morte subita et inopinato abreptae

valde defletae;

—

FILII PARVULI,

percari, multo, meritoque dilecti,

docilis, alacris, solertis,

spei eximiae,

aeque subito direpti;

amore conjugis, parentisq(ue) superstitis

memoriae

consecratum.

—

MARIA CAROLINE,

WIFE OF WALTER KIRKPATRICK ESQ.

Born Oct. 12th, A.D. 1798,

Died Oct. 6th, A.D. 1826.

—

EUGENE WALTER KIRKPATRICK,

Born May 4th, A.D. 1825,

Died July 23rd, A.D. 1828.

Nineteenth-century Americans, no strangers to death at an early age, still felt a heavy blow when it took one of their own. Maria’s sister described Walter in the wake of his first bereavement as “a silent deep, deep mourner,” and “a wreck of a once happy being,”[17] yet the text which he chose for this monument must have owed more to its Roman antecedent than a fragment of its opening line. Perhaps in Horace, especially in his words “linquenda tellus et domus et placens uxor” (21-22), Walter Kirkpatrick found both the power to accept and the ability to speak fittingly and nobly of what he had briefly had, and lost. Perhaps in Horace, Parsippany at last found a poet worthy of its Muse.

Copyright © 2014 by Gregory J. Guderian

^ 1] The principal collection of Julia Ann Cobb’s letters forms part of the Smith Family Papers at the New Jersey Historical Society (hereafter “NJHS”), Manuscript Group 824, Box 83, folders 1 through 4. Maria Caroline’s letter (found in folder 1) is addressed “To Mr. Walter Kirkpatrick, Morristown,” signed “Adieu yours – Caroline,” and dated “March 16 – Mon – Evening – 12 o[clock],” namely in the early hours of Tuesday, March 17, 1819.

^ 2] I. S. Lyon, “Recollections of an old cartman – No. 7. Sylvester Graham.” Newark Daily Journal (May 31, 1871), 1:7-8. Reprinted in Isaac S. Lyon, Recollections of an old cartman (Newark 1872), 33-36.

^ 3] Helen Graham Carpenter, The Reverend John Graham of Woodbury, Connecticut and his descendants (Chicago 1942), esp. 183-184. Soon after settling in Parsippany, Sylvester Graham was appointed to give the reading of the Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1817, the eve of his twenty-third birthday. Palladium of Liberty (June 26, 1817), 3:3. Graham had a more prominent role in the following year’s celebration, delivering a spirited oration “in which the odiousness of vice, and the impolicy of animosity, were denounced with eloquence.” Palladium of Liberty (July 16, 1818), 3:1; cf. Palladium of Liberty (June 11, 1818), 3:4, (June 25, 1818), 3:4.

^ 4] The Supplement was later included in a New York “benefit concert” given in 1821 for Samuel Woodworth, a poet, publisher and friend of Graham. National Advocate (February 19, 1821), 3:1, (February 20, 1821), 3:3. Graham gave at least one other recital featuring the Supplement in Morristown in 1822 (see note 13 below). Nonetheless the text seems to have been preserved only in Lyon’s vignette of Graham. Lyon saved many of Graham’s other writings in a scrapbook (its present whereabouts unknown), and probably kept the text of the Supplement among them. The mention in Edmund Drake Halsey, History of Morris County, New Jersey, with illustrations and biographical sketches of prominent citizens and pioneers (New York 1882), 227, of “an allegorical burst of rhyme which was printed, and formerly quite largely read in the vicinity” quite possibly refers to Graham’s Supplement to The Passions.

^ 5] While I have found no direct proof for the assertion in Halsey’s History, 227, that Graham was a suitor of Maria Caroline Cobb, there is clear evidence of a connection with her sister Julia Ann.

In a letter to her cousin Elizabeth Kirkpatrick, of approximately the same date as Maria’s to Walter, Julia wrote enthusiastically about the upcoming Exhibition (“The performance is expected to be something extra’,” i.e. extraordinary). From this letter we also learn that the program of March 19, 1819, was to be repeated twice the following week. Two other letters from Julia of that year – one dated May 9 and one datable to June – refer to Graham by name. Julia’s mention in a letter to Walter Kirkpatrick (dated simply August 17) of “the Percipany Poetaster” who had once offered her a handkerchief is almost certainly another reference to Graham. The four letters are in NJHS Manuscript Group 824, Box 83, folders 1 and 2.

The Cobb Collection at the Morristown National Historical Park Library possesses another, intriguing letter (in Box 5, folder 10) written by Julia Ann Cobb at Orange Spring – probably in 1823, when Graham had left Parsippany but was still in New Jersey – bemoaning the interference of family members in her dalliance with an unidentified man, whom the now-married Maria Caroline labelled “that fool, that fop”: “she charged me with corresponding with him … if I have it would be no more than she has done before me. … M[aria] has only to look back to her young days, & she will see many more imprudent steps or rather rashly taken than even Julia has.”

There are, finally, published verses by Graham whose titles and texts allow them to be construed as referring to one or the other of the Cobb sisters (for example, “To Julia Ann, A Song,” signed “The Græme,” in Ladies’ literary cabinet [May 19, 1821], 16:2), but as historical evidence Graham’s poems must be treated cautiously.

^ 6] In 1809 Esther and Elizabeth Scribner opened the young ladies’ boarding school in Morristown where Maria was enrolled at the age of 13. They advertised a litany of subjects including geography, history, writing, drawing, painting, music and French. Genius of Liberty (March 28, 1809), 3:2, (November 14, 1809), 3:3; cf. Genius of Liberty (November 6, 1810), 3:1, (April 23, 1811), 2:2. Walter Kirkpatrick wrote in July 1812 to Maria, then a pupil at the Scribners’ school: “You told me in your last, that you did not expect to stay longer than the present Quarter. I would be glad to know whether you will only quit boarding with Miss Scribner, or will leave the School entirely.” A letter from Walter one year later shows that she was again residing in Parsippany. See the following note for the dates of these letters.

^ 7] The four letters to Maria Caroline Cobb, dated January 31 and July 6, 1812, January 20 and July 17, 1813, are preserved in the alumni file for Walter Kirkpatrick, Class of 1813, Undergraduate Alumni Records, 1748-1920; Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, Princeton University Library.

^ 8] Letter of Henry Clay at Washington, D.C., to Walter Kirkpatrick at Ashland, Lexington, Kentucky, dated March 28, 1816, in NJHS Manuscript Group 31, Box 1, folder 46. The body of the letter was printed in Melba Porter Hay, ed. The papers of Henry Clay: Supplement, 1793-1852 (Lexington 1992), 52-53. See also James F. Hopkins, ed. The papers of Henry Clay 1815-1820 (Lexington 1961), 2:392. The reason for Kirkpatrick’s 1815-16 sojourn in Kentucky is made plain in the autobiography of his predecessor, who referred to him as “Mr. Kilpatrick.” William Stickney, ed. Autobiography of Amos Kendall (Boston 1872), 142.

^ 9] The note is found on an undated slip of paper inside the diary of a journey from Parsippany to Ithaca, New York. Kirkpatrick, Walter: Diary, 1821; Howell Family of New Jersey Papers, Box 3, folder 12; Manuscripts Division, Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, Princeton University Library.

^ 10] New-Jersey Eagle (September 28, 1821), 2:2, 3:4.

^ 11] “Such is the case with him, whose soul of fire, / Love, virtue, fame, benevolence, inspire, / Till Envy’s storm around each effort breeds, / And Slander’s lightnings blast his noblest deeds; / While e’en the miscreants he has greatly bless’d, / With lies insulting, his proud course molest.” “To Caroline Matilda.” Ladies’ literary cabinet, n.s. 2:3 (May 27, 1820), 23:1.

^ 12] “The grave of sorrow’s child. Dedicated to the sympathies of the broken-hearted.” Ladies’ literary cabinet n.s. 3:18 (March 10, 1821), 143:3-144:1.

^ 13] The Palladium of Liberty (April 18, 1822), 3:3.

^ 14] “Graham’s Farewell to Parsippany.” The Palladium of Liberty (May 30, 1822), 1:4-5. Reprinted in New-Jersey Eagle (June 7, 1822), 1:4.

^ 15] Two valuable sources for Graham’s clerical career in New Jersey are found among the Graham family papers, William L. Clements Library, The Unversity of Michigan. The first is a book of letters transcribed by Graham, “Testimonials concerning the character of Sylvester Graham, relative to his entering the Christian Ministry,” in Box 1, folder 18. The other is a defense of Graham, addressed to the Presbytery of New Brunswick in 1829 by the congregation in Bound Brook which had employed him. Box 2, folder 30. According to Isaac Lyon, Graham did once return to Parsippany as a preacher and, being refused the use of the old church (a new one having been built in 1828), gave a “very eccentric” sermon in the school room of the Academy, where “he preached to a much larger audience than he had ever played to in the room overhead.”

^ 16] See note 12.

^ 17] Letter from Julia Ann Cobb to Mary (an unidentified friend), dated Parsippany, August 15 [1827]. NJHS, Manuscript Group 824, Box 83, folder 3. Fourteen years before, Kirkpatrick had sent condolences to Maria on the death of a young companion, reminding her of “the solemn truth that no age from death is free.” Letter from Walter Kirkpatrick to Maria Caroline Cobb, dated Nassau Hall July 6, 1812. Walter Kirkpatrick, Class of 1813, Undergraduate Alumni Records, 1748-1920; Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, Princeton University Library.

-

February 27, 2023 at 3:08 pmwith dedicated server